This project began from my desire to give voice to the unstable position I experience while living abroad as an immigrant—where my existence is constantly shaped by shifting social conditions, legal systems, and the data I am asked to submit. Although I live as a physical individual, the outline of who I am often seems to be defined, processed, and transformed through text-based information. This tension became the starting point of my artistic practice.

In this project, I generate daily self-portraits using AI image technology. By inputting various pieces of personal information required for residence permit applications—such as birthplace, religion, eye color, and height—into the AI, a new portrait is generated each day. What is particularly striking is the AI’s ability to produce different images even from the same information. This destabilizes the notion of a fixed self-image and reveals how recognition—both of oneself and by others—remains fluid and unstable.

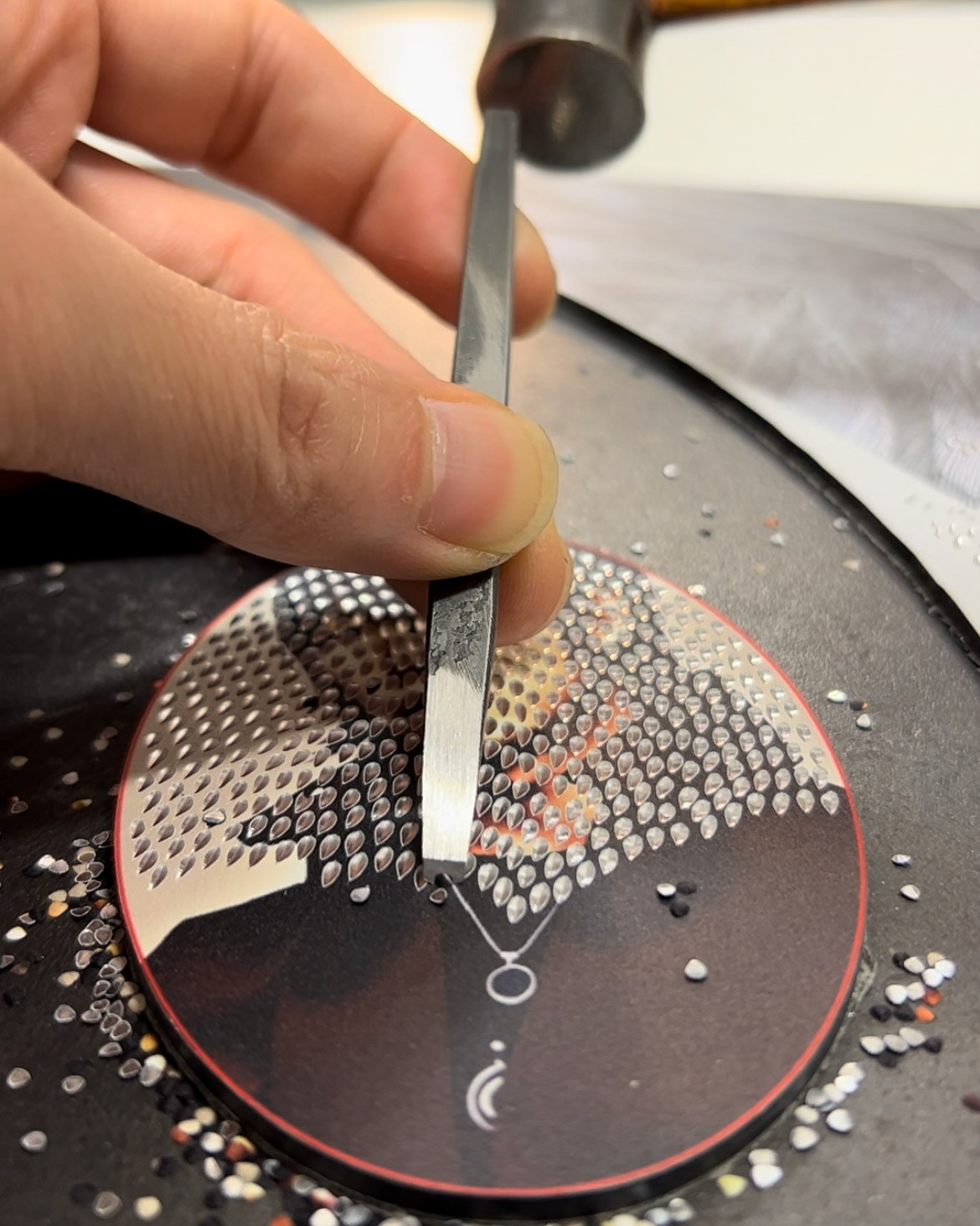

Yet what matters here is not the act of generation itself. I subject these AI-generated images to the traditional craft technique of metal engraving, physically scraping into their surfaces with my own hand. Through this intervention, the images and information are partially erased, obscured, and distorted. This process of resisting and subtracting from what digital technology produces becomes a critical gesture against our blind trust in, and dependence on, information. It inscribes a tension between the machine and the human body—one that emerges only through the physical act of engraving.

This question connects deeply to the history of portraiture. In the West, portraits were once commissioned by monarchs and aristocrats to display power and beauty, often shaped by the artist’s compliance and deliberate manipulation. With the invention of photography in the 19th century, portraiture temporarily shifted toward recording “reality” as it was, yet later, with the spread of Photoshop and editing apps, it returned to serving as a tool for idealization. Today, AI pushes this tendency further: trained on vast datasets, it reflects unconscious desires and social norms, automatically generating images of how one “should” appear. This engenders a sense that one’s own image is no longer under one’s own control.

Most AI-generated portraits bear little resemblance to me. Yet, as I live abroad and am repeatedly required to submit personal data, I have come to feel that it is this “textual information” itself that defines me. In other words, in our present moment, the self is no longer grounded in visual likeness but increasingly configured as an accumulation of data. This series casts a critical gaze on that condition, questioning the relationship between text, image, data, and the figure of “the self.”

The project operates under the following rules:

- Only one AI-generated portrait may be created per day.

- The same set of personal information is always entered as the prompt for image generation.

- At the beginning of each month, I craft a new chisel myself and use it for all works created during that month.

- If a mistake occurs during the engraving process, the work is destroyed and restarted.

- On the reverse side of each completed work, the date of image generation is engraved.

- The project ends the moment the AI generates an image that closely resembles the artist himself.

- Each generated image is automatically classified by the AI into one of five formats—ring, earring, necklace, brooch, or wall-mounted work. The AI provides a brief comment explaining its choice, and the artist accepts this decision without intervention.

These rules gradually strip away the artist’s freedom to choose, embedding within the daily practice of making a structure that confronts fundamental questions: the relationship between human and machine, the rights of generation and selection, and, ultimately, who it is that constructs the image of “the self.”

本プロジェクトは、海外で移民として生活する中で、社会情勢や制度の変化に常に影響を受ける不安定な立場に置かれていることから、「声をあげたい」という実感とともに始まりました。個人として存在しているにもかかわらず、その輪郭は制度に提出する文字情報やデータによって定義され、管理され、変容していく、そんな経験が、この制作の出発点になっています。

本プロジェクトでは、AIによる画像生成技術を通じて、私自身のポートレートを生み出しています。滞在許可証の申請に必要とされる出生地や目の色、身長、宗教といった個人情報をAIに入力し、日々新たな像が生成されていきます。その際、同一の情報を与えても毎回異なる像が立ち現れるというAI特有の性質は、固定化された自己像の概念を揺さぶり、自己や他者からの認識がいかに流動的であるかを浮かび上がらせます。

しかし、ここで重要なのは生成そのものではありません。私はそのAIの成果物に対して、伝統工芸である彫金技法を用い、自らの手で削り取る行為を重ねています。デジタルな表象に物理的な抵抗を加えることで、情報やイメージを不可視化し、見えにくくし、あるいは歪めています。最新のテクノロジーが生成する像を、身体を介した手仕事によって抑圧し、削ぎ落とすこのプロセスは、私たちが情報に対して抱く盲目的な信頼や依存に対する批評的な身振りです。そこには、人間の手が加わることによってのみ立ち上がる、機械と身体の緊張関係が刻まれています。

この問いは、ポートレートの歴史にも接続します。西洋において、ポートレートはかつて王侯貴族が権力や美を誇示するために画家や職人に依頼したもの(絵画やジュエリー)であり、そこには「よく見せる」ための操作や忖度が存在しました。19世紀に写真が登場すると、ポートレートは一時的に「ありのまま」を記録する手段へと転じましたが、その後はPhotoshopや加工アプリの普及によって再び理想化の道具となりました。そして現在、生成AIは膨大なデータを学習し、私たちの無意識的な欲望や社会的規範を反映させながら、自動的に「こうあるべき姿」を生成しています。そこには、もはや自分自身の像を自らの手で制御できないという感覚が生まれています。

AIによって生成された像の多くは、私自身とは似ても似つかないものです。しかし異国で生活するなかで頻繁に提出を求められる個人情報の積み重ねによって、次第に「文字情報」そのものが私を定義しているのではないかと感じ始めました。つまり、今日において自己像とは視覚的表象に先立ち、データの集合として規定されるものへと変容しつつあるのです。本シリーズは、この状況に批評的なまなざしを投げかけ、文字・画像・データと「私」という像との関係を問い直そうとしています。

そして本プロジェクトは、以下のルールによって運用されています。

・AIによるポートレート生成は、1日につき1枚のみとします。

・画像生成には、常に同じ個人情報のプロンプトを入力します。

・月ごとに新しい鏨(たがね)を一本制作し、その月に生成されたすべての作品に用います。

・彫り工程において失敗が生じた場合、その作品は破棄し、最初からやり直します。

・完成作品の裏面には、画像生成日を刻印します。

・作家本人と酷似したAI画像が生成された時点で、このプロジェクトは終了します。

・生成された画像は、AIによって自動的に「指輪・イヤリング・ネックレス・ブローチ・平面作品」の5形式のいずれかに分類され、AIは選定理由を簡潔なコメントとして添えます。作家はその判断に介入せず、結果を受け入れます。

これらのルール群は、作家に残された「選ぶ自由」を徐々に剥ぎ取りながら、人間と機械の関係性、生成と選定の権利、そして「私」という像が誰によって形成されるのかという根源的な問いを、日々の制作行為そのものに刻み込む構造になっています。

Portrait jewelry / brooch, 90x63x10mm, ring, 60x42x25mm / 2023

Aluminum composite panel, UV direct print, Image Generation AI, stainless steel, silver

アルミ複合板、UVダイレクト印刷、画像生成AI、ステンレス、銀

Portrait jewelry / necklaces, 70x6mm, 620mm(length), earrings, 50x35x13mm

Aluminum composite panel, UV direct print, Image Generation AI, silver

アルミ複合板、UVダイレクト印刷、画像生成AI、銀

Portrait (12 Mar 2023) / two-dimensional work, 490x350x5 mm / 2024

Aluminum composite panel, UV direct print, Image Generation AI

アルミ複合板、UVダイレクト印刷、画像生成AI